A Longhouse, Sheep’s Head, West Cork. 2020.

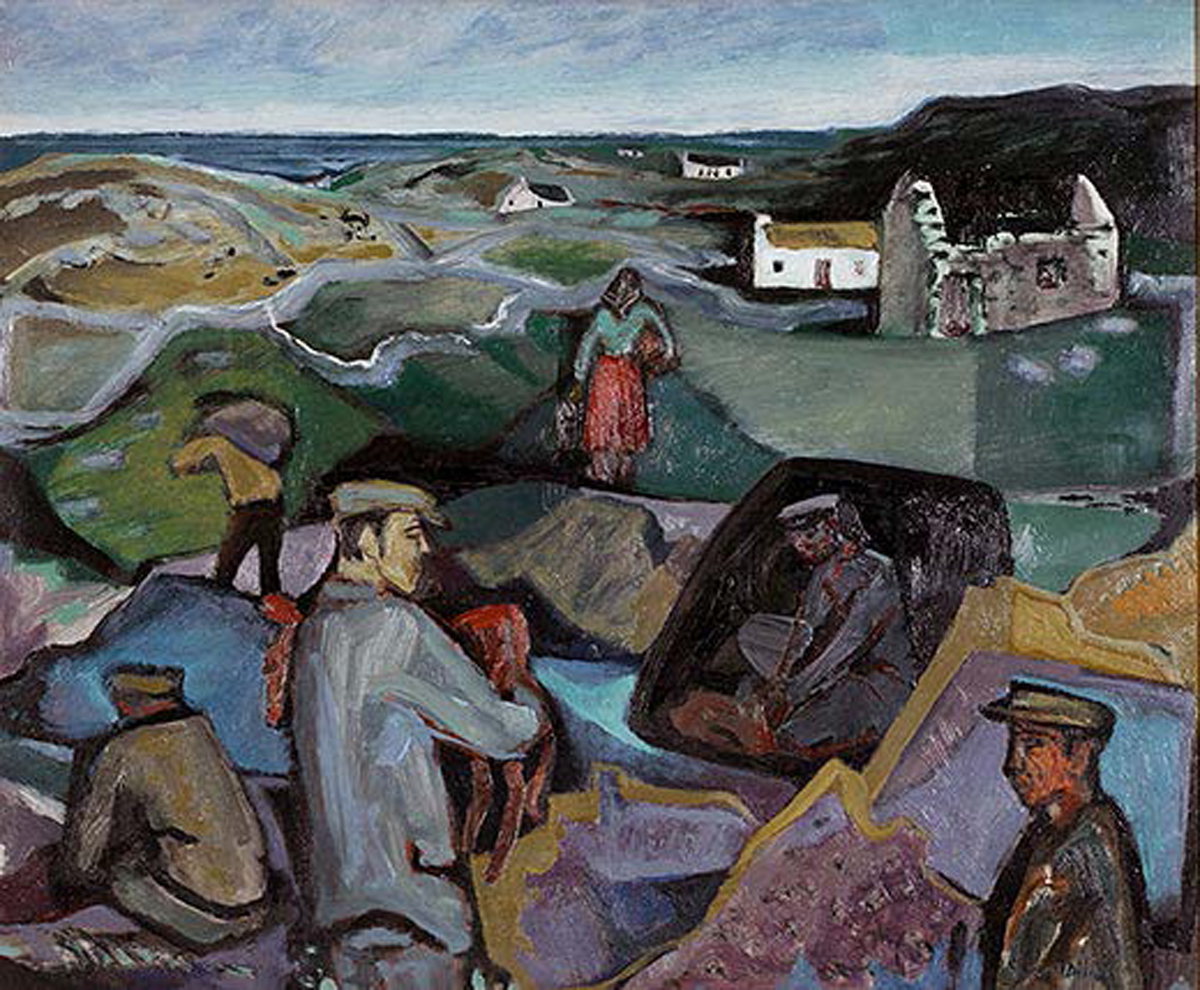

The site for this project is in an area of outstanding natural beauty on the West Cork Atlantic coast. The area is defined by a landscape of rugged sandstone coastline and carefully tended fields with dry laid stone walls. This landscape still retains a romantic beauty as depicted by early C20th Irish artists like Gerald Dillon and Paul Henry. A rural scenery, it is an image of the countryside and the community, and their interwoven relationship. The charming quality of this place is constructed from the natural and the man-made. The dry-stone boundary walls, narrow carriage ways, and ruinous stone cottages are as much a part of one’s memory as are the undulating hills, coarse grass fields, wild sea and big sky.

Irish planning regulations to build in remote rural areas are rightly strict. Similar to the Paragraph 79 country house clause in the UK, applicants should demonstrate projects are of outstanding quality and a progression of type, asking of oneself the question of what it means to build in rural Ireland in the C21st. As a reaction to ‘bungalow blitz’ the local planning authority restricts development to sites with previous habitable buildings, whether intact or ruined. This means a lot of the charming ruins that once populated the area are being developed and transformed beyond their original appearance to enable the necessity for new rural family dwellings.

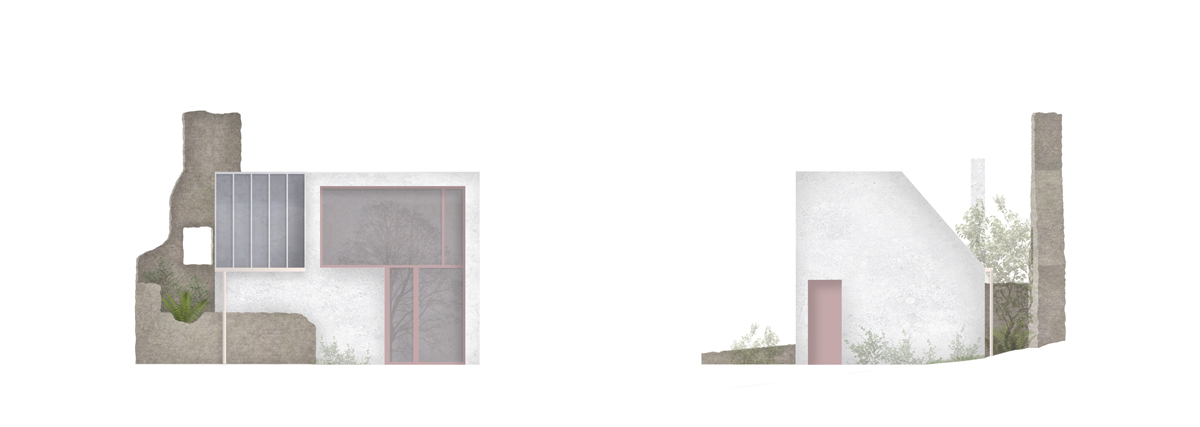

The design carefully avoids many recent examples where the renovation and refurbishment of these existing ruins is taken to a point too far where the existing original character is overcome and consumed within the body of the new proposal making the original all but invisible.

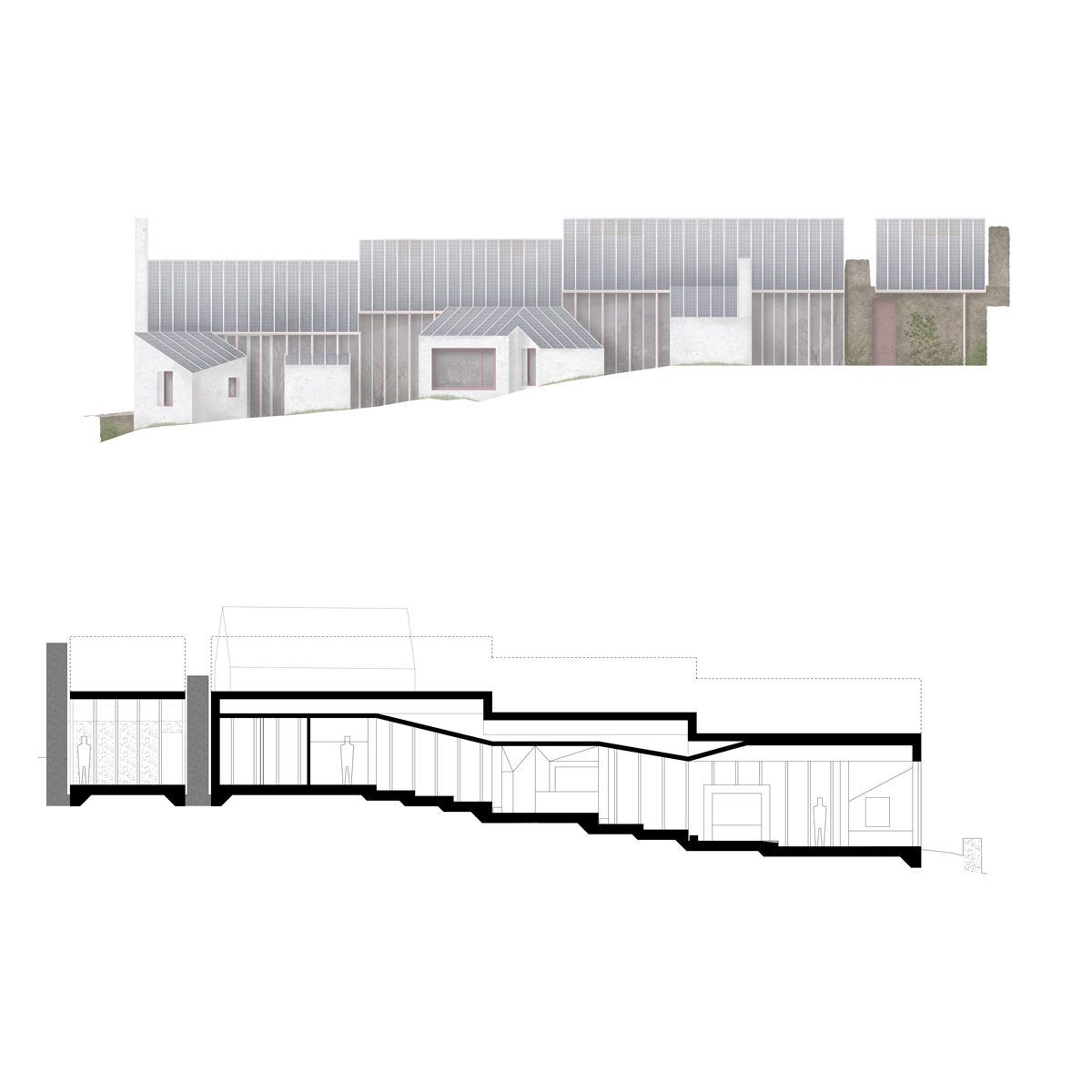

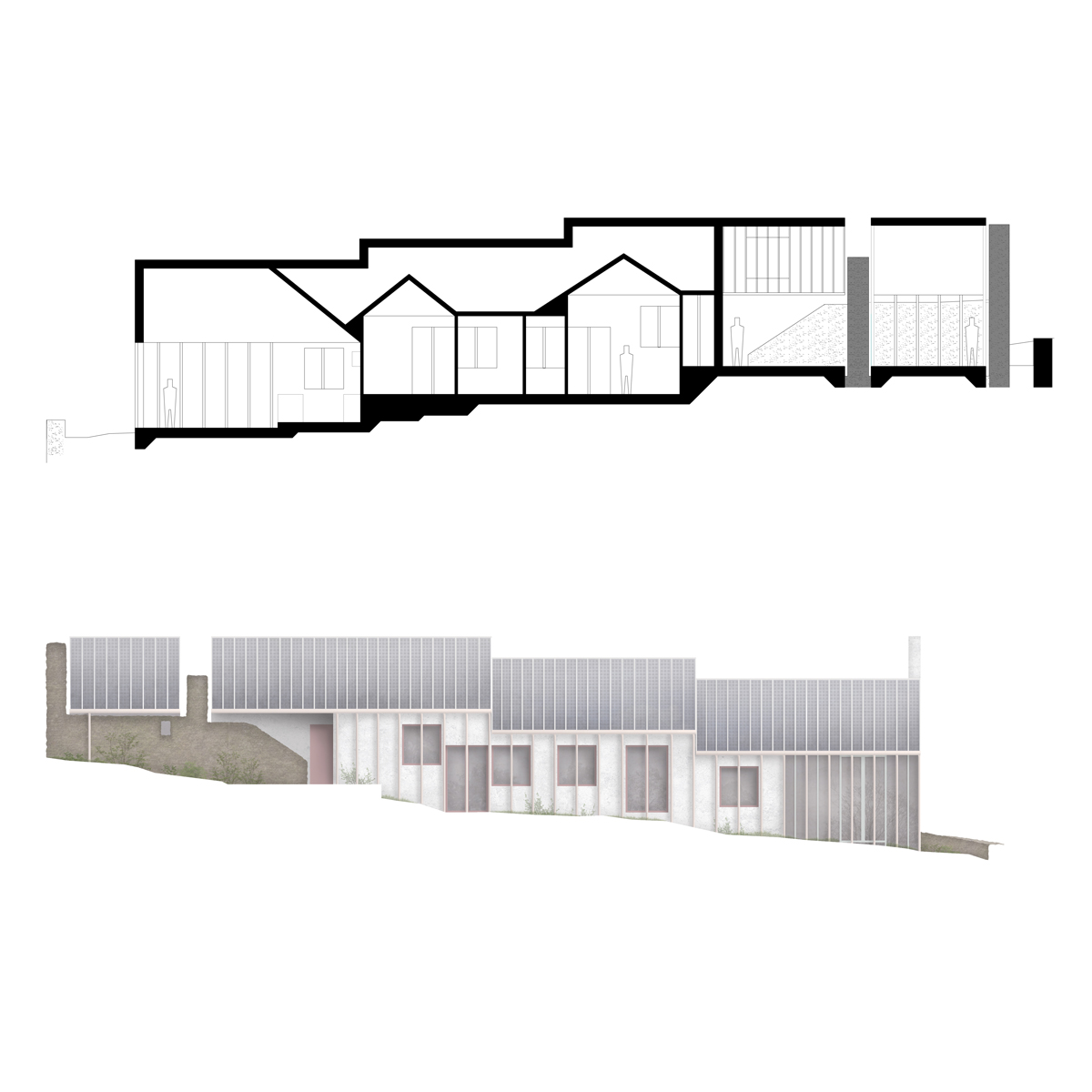

Within the existing walls of the East ruin a delicate new glass and frame structure is inserted internally to provide conditioning and comfort without concealing the patina of the aged stone walls behind. The old field stones so carefully stacked to form the massive stone wall are kept visible through an insulating glass which provides the required U-value.

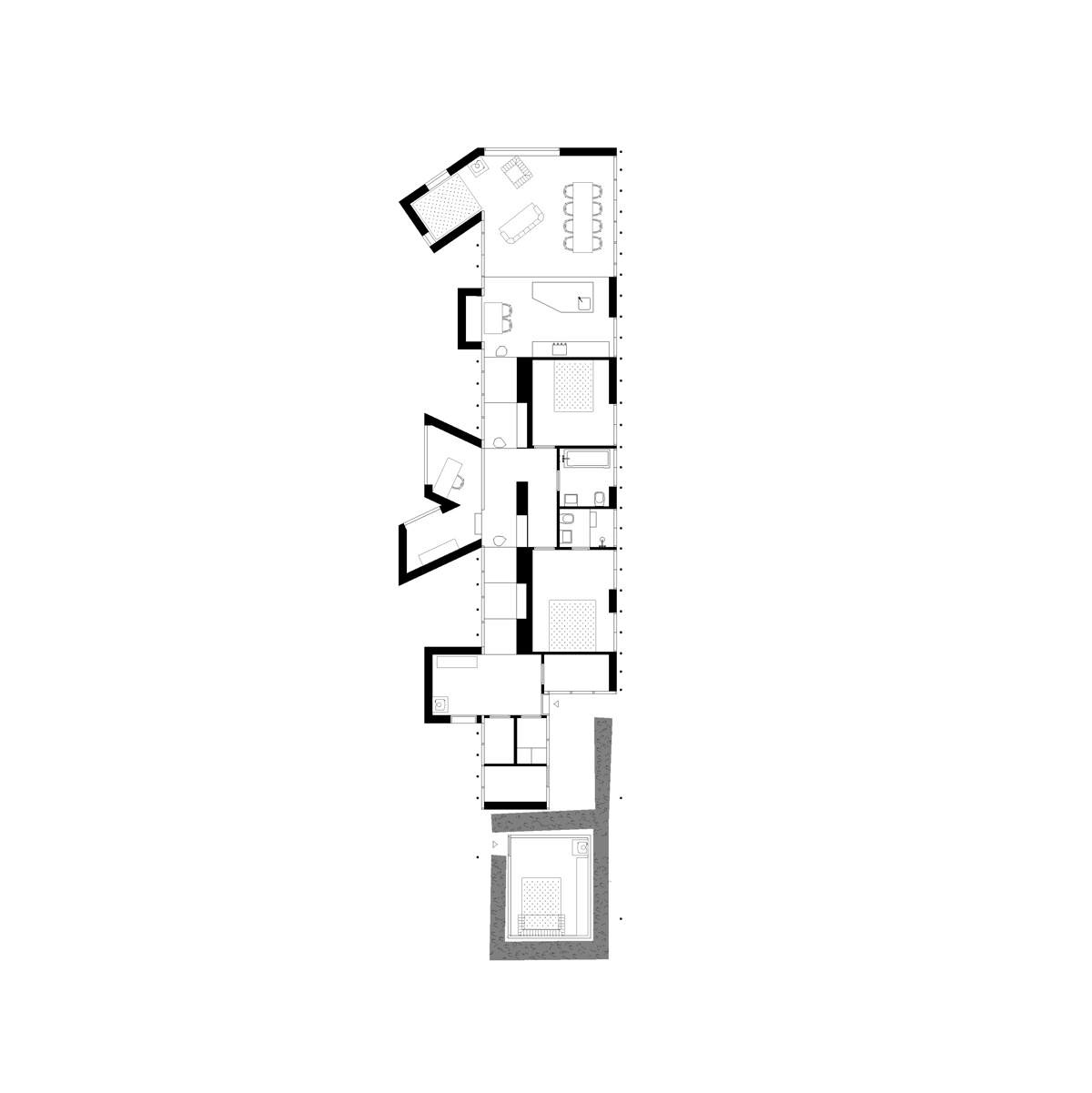

The proportion and width of this existing structure sets out the dimension and scale of the extruded extension.

The living spaces are directional, following the topography and the view. A ceiling is draped internally with a rhythm and fall separate to that of the stepped exterior roofline. Off the stepped library, various outshots protrude cranked for views and privacy, pochéd to hold more intimate functions as cloak cranny, breakfast nook, study cranny and ingle nook.

Private chambers for bedrooms, bathroom and ancillary functions are in more static volumes. These rooms are vaulted and vary in height and proportion to determine an appropriate atmosphere and hierarchy of use. Externally the long bar divides the site into gardens of different character, climate, and function. Like typical long houses the interior plan is one room wide with immediate connection to the outside.

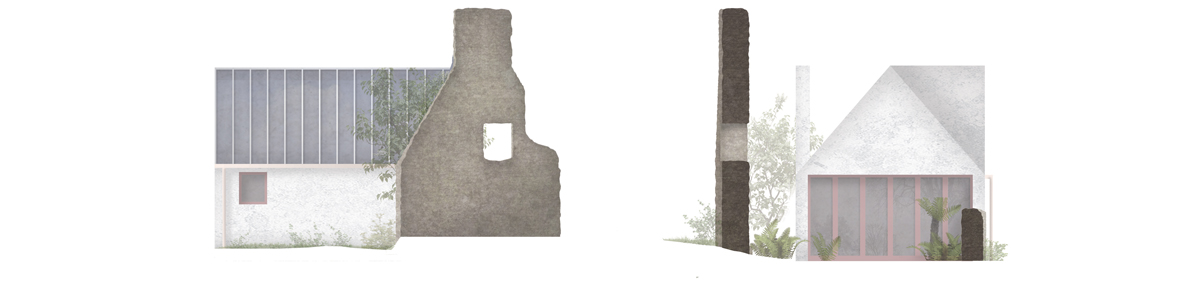

The project references the optimism of the early hi-tech projects of Foster, Rogers, and Team 4, using advanced materials, technology, and systems. Technology is not used as an application but instead inherent to the building and architectural fabric, like at the Team 4’s projects at Creak Veen House and Murray Mews. Importantly, unlike hi-tech, the project does not attempt to fetish efficiency but instead to take delight in questions of function, redundancy, and the applied arts. Like the earlier more ambiguous projects at Murray Mews and Creek Veen this leads to a more domestic aesthetic that is both a little hi-tech and a little DIY. In this manner 58 polychromatic powder coated aluminum downpipes, both act as a façade and as a sustainable way to distribute surface water run-off directly into the ground without the need for heavier infrastructure. The shallow colonnade they form is detailed to give the impossible impression of holding the weight of the roof above whilst also acting as a screening device to provide privacy to the glazed curtain walling behind.

Glass is chosen as a material more for its specular qualities rather than its transparency. A glass photovoltaic roof reflects the sky and the ever-changing weather. The glass PV panels are the building material, forming the roof rather being applied onto one. Aluminum patent glazing bars are fitted with PV glass sheets as a rainscreen over a single ply pitched roof. The photovoltaics generate enough output for the house and studio and the excess electricity is supplied back to the grid.

The PV glass tiles and patent glazing bars recall the DIY quality of the greenhouse but also the vernacular roofing materials of a repeated tied thatch, or lapped slate stone roof, albeit translated now for the C21st.

Other sustainable strategies for water supply and drainage are employed so that the house is completely self-sustaining, requiring no connection to existing public infrastructure. In this way the house is inherently sustainable with the lowest embodied and operational carbon strategy provided by locally sourced materials and off-grid energy generation and mechanical servicing.

In this respect the architecture and the technical resolution is one. The design hopefully demonstrates that if all architecture is to be sustainable one must not look at this technology as applications, but rather as the building material.

Esta entrada aparece primero en HIC Arquitectura http://hicarquitectura.com/2020/07/david-leech-a-longhouse/

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario