| Pascal Deschenaux

| Pascal Deschenaux

| 2016 | Master Thesis | ETH

| Professor: Studio Adam Caruso

Standing on the shoulders of giants

I do not understand the appeal of “newness”. It is not that I have an aversion to the idea, but rather the belief that this is not the goal we should be striving towards. I think a mistake made by this generation is that we get things mixed up and believe that newness actually expresses important paradigms such as originality, revolution or beauty. But how can a work be original if it is not based upon past experience? If those in our field would accept that architecture is strongly inspired by existing designs, this would already be a great step forward and liberate the debate about where to go next. I believe that true beauty and originality is to a great extent inspired by the past, recomposed and expressed in new ways. Additional layers of cultural references and clear conceptual ideas can make a work richer and give it groundedness and complexity. I believe that a truly great building does not try to be unique or new, but strives to be specific within its given culture, formally meaningful in its spatial context and beautiful through its material and composition.

A historical fossil

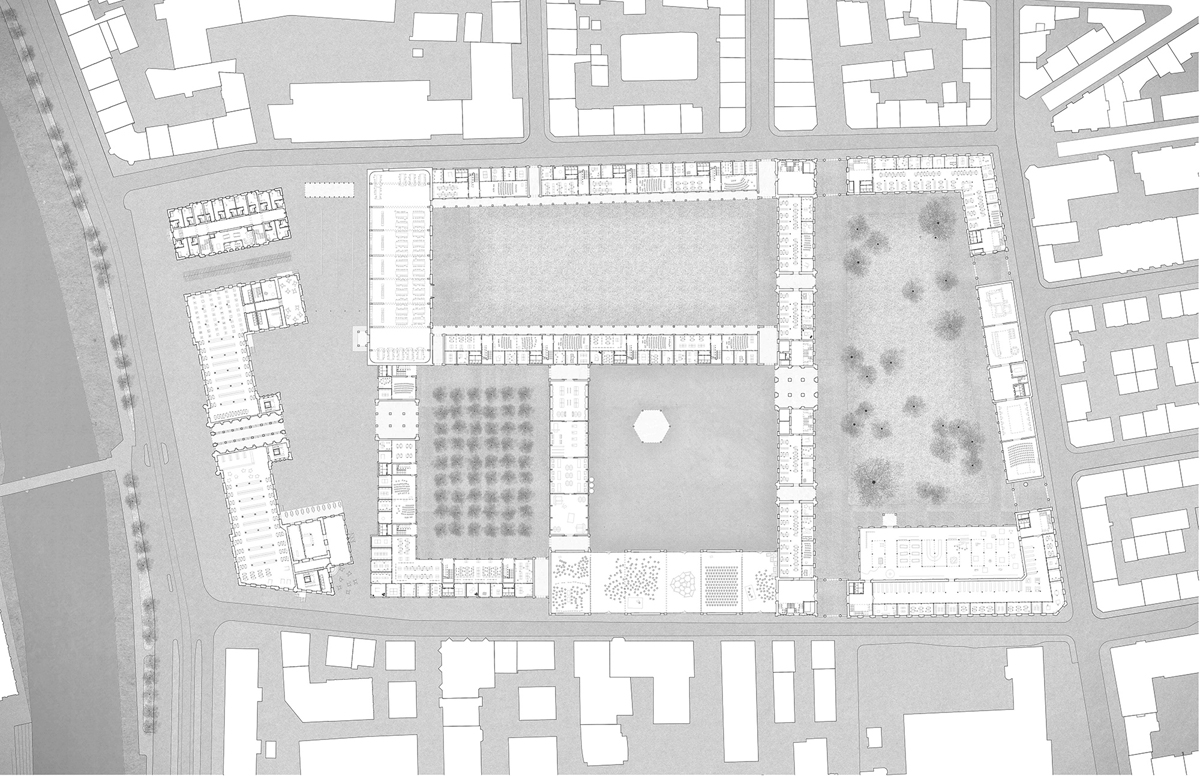

The site of the Kaserne in Zurich lies half-finished in the fourth district, a historical fossil which did not adapt to the city around it: the parade grounds are too big to be enjoyed, the Kaserne too bulky. However, the architectural ensemble remains historically relevant and thus cannot be erased. The only solution is transformation. The new architecture school that is proposed in this project will work as an inhibitor to reconcile the Kaserne to its urban surroundings and through this process it will obtain permanence and urban relevance.

Cambridge visits Zurich

Thomas Neville, Master of Trinity College Cambridge, had a great vision for his school at the beginning of the 17th century. He created a great new college for Trinity by using existing structures from older colleges and linking them together with new buildings to form two great courtyards. He transformed the existing structures quite freely, destroying buildings that did not fit in with the scheme, adapting existing facades, and keeping some parts untouched. As a whole, Trinity offers a variety of different heights, proportions, facades and eras.

The new architecture school re-uses Neville’s strategy. It links the Kaserne, the warehouses and the police building with new buildings that create four great courtyards. Most of the new bars consist of design studio spaces for professors, staff and students. The studios also take possession of the existing warehouses, allotting the same function to different spaces. In between the bars, more important buildings such as auditoriums and food courts enrich the plan with a new-found hierarchy.

A sequence for the idle stroller

In contrast to Trinity, the new courtyards remain open to the city day and night. Although conscious that he is in the architecture school, the idle stroller will be able to appreciate a spatial sequence of different courtyards. The identity of these courtyards is not defined by function but much rather by size, proportion, surrounding facade and landscape. They become part of the city, paths for people to cross or places to take a break. They are an open part of the city and offer an alternative to the Volkspark.

Working around the “set”

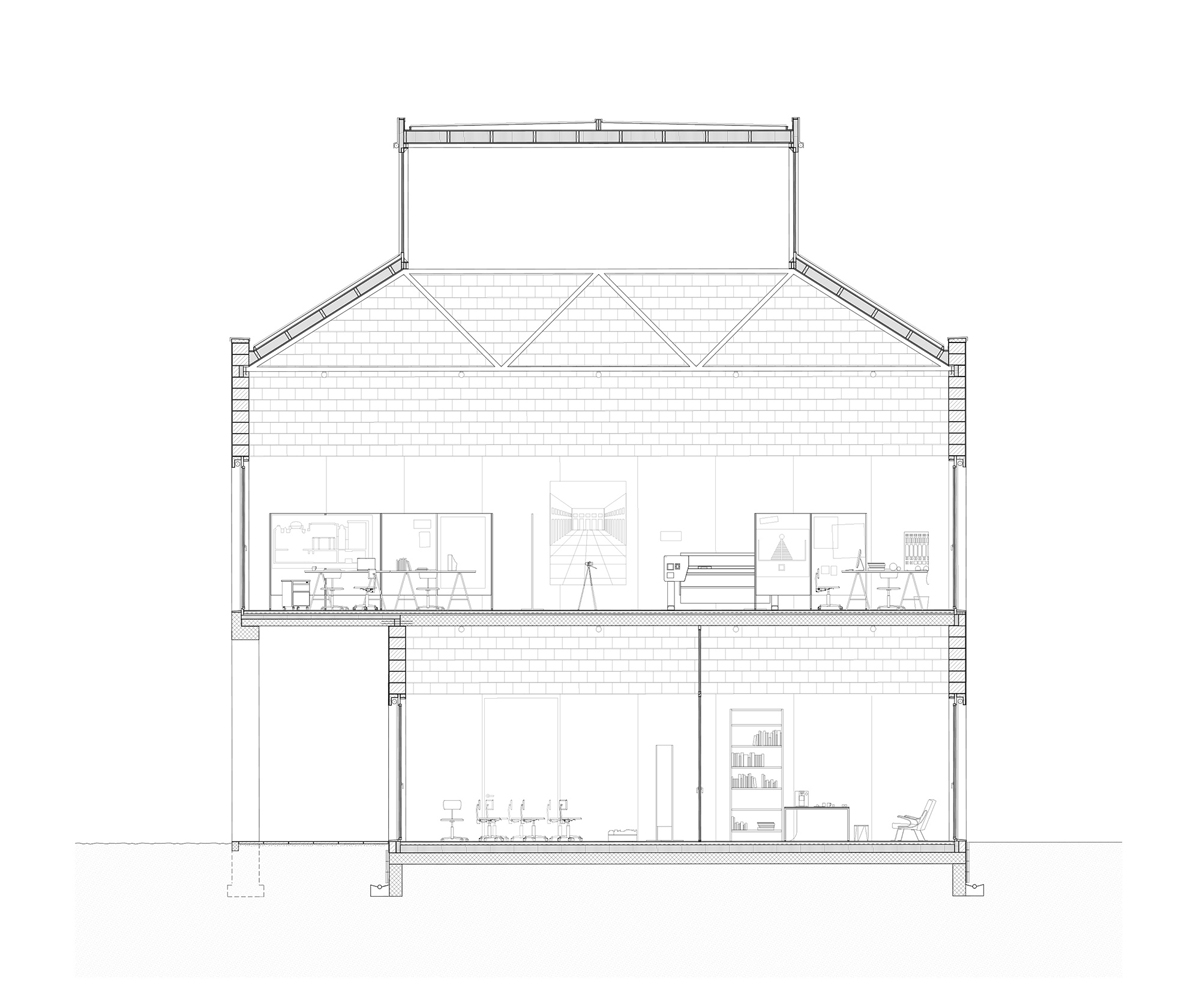

Each studio has its own address, clearly visible from the courtyards. It is organized around a generous staircase, the ‘set’. The professors, staff and students all work on an open-space first floor. No clear spatial differentiation is made between these groups. On the ground floor the set leads out to two sides of smaller, more enclosed rooms. Each professor decides with his students how they want to use the space.

The warehouse in disguise

Although most of the facades of the existing Kaserne ensemble present formal and partly distinguished facades, the insides are the exact opposite. They are very basic, industrial, and their structure is left visible. Even the Kaserne itself with its stone facade has a more pragmatic steel structure inside. This principle of an industrial building in formal attire is used to give an architecture to the new additions. From the outside, the new buildings possess a composed, almost pedagogical, hierarchy in the facades. Inside, materials are raw and uncompromising. Wooden planking, bare insulation brick and steel structure reveal the true tectonic nature of the buildings. The inside industrial spaces possess all the qualities needed for a design studio: tall ceilings, zenithal light, large surfaces for groups, a lot of space to think.

Blurring the boundaries

The existing buildings and the new additions integrate into a whole. The design is neither based on contrasting old and new nor on copying the old into the new. It tries to conciliate the two parties through an exchange of architectural language, similarities in atmospheres, and creation of new outside spaces. It unifies the two parties by using the same rhythm of windows, by changing window formats or by using common proportions.

Esta entrada aparece primero en HIC Arquitectura http://hicarquitectura.com/2017/12/pascal-deschenaux-two-way-tensions/

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario